The history of hair removal through the ages

Hair removal can be performed for cultural, aesthetic, hygienic, sexual, medical or religious reasons. In almost all human cultures, forms of hair removal have been used since the Neolithic era. The methods used to remove hair vary by era and region. Although the choice to remove body hair is now a personal preference, it is a practice shaped by centuries of history. Today, hair removal has become one of the most popular beauty treatments.

Antiquity

Archaeologists have found evidence that humans began shaving around 100,000 B.C. To this end, in the beginning they used two shells as tweezers, with which they pulled out the hairs one by one, an extremely painful and time-consuming affair. Why? Because of the low temps, wet beards could freeze, causing frostbite wounds. Another reason for this early procedure was to minimize breeding grounds for lice, fleas and small rodents, while another was to eliminate the beard as a handhold during battles. However, the oldest razors - consisting of a sharp piece of flint that one had to scrape across the face until all hair was gone - date back as far as 3,000 BC.

Shells for hair removal

A clamshell, like tweezers, has been used for hair removal since prehistoric times.

Cave paintings have been found depicting beardless men who possibly removed their hair with clamshells or flint knives. Both tools became blunt with repeated use, requiring frequent replacement, much like the disposable razors on the market today.

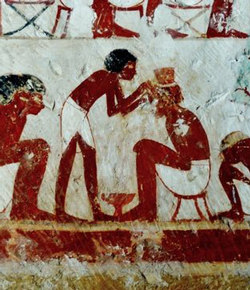

Ancient Egypt (3,300 BC - 332 BC)

According to the Greek historian Herodotus, Egyptians were fanatical about personal hygiene, especially when it came to body hair. Because they lived in a hot, dusty and sweaty country, lice - especially head lice - were a constant problem. Lice not only cause discomfort, but they can also transmit diseases, especially to children. Egyptians shaved their heads to remove the breeding ground for lice and, according to Herodotus, Egyptian priests shaved their entire bodies to get rid of lice and other impurities.

The priests of the gods in other lands wear long hair, but in Egypt they shave their heads: among other men the custom is that in mourning those whom the matter concerns most nearly have their hair cut short, but the Egyptians, when deaths occur, let their hair grow long, both that on the head and that on the chin, having before been close shaven.

Even the Old Testament points to the importance of shaving and cleanliness in Egypt. In Genesis 41:14, when Joseph was brought before Pharaoh, it was important that he had shaved first:

Then Pharaoh sent and called Joseph, and they brought him hastily out of the dungeon: and he shaved himself, and changed his raiment, and came in unto Pharaoh.

But despite the obsession with cleanliness and hygiene, elites still liked the 'long-haired' look when it came to acts of worship and displaying eminence. This is where wigs came in: animal and other people's hair were used to make wigs for the rich, often elaborately decorated and styled with luxurious oils and fragrances.

The Ebers Papyrus, an ancient Egyptian medical text dating from around 1550 BC, mentions that ancient Egyptians also used depilatory creams. It contains a recipe for a cream made from hippopotamus fat and turtle shell. Another cream was made from boiled bird bones, fly manure, lard, sycamore milk, gum and salt.

It (i.e. the hair) should be removed as follows: the shell of a turtle, it will be boiled, it will be crushed, it will be added to the fat of the leg of a hippopotamus. One anoints it with it, very often.

Remedy for removing hair from all body parts Boiled bones of the gbg bird, fly manure, lard, sycamore milk, gum, a lump of salt. Warm up. Apply.

Razors are also well known. However, it is sometimes unclear whether these are razors that cut through hair or whether they are more like scrapers used to remove hair after it has been softened. Egyptian toiletries usually had more than one type of razor. Throughout much of Egyptian history, flint was used for cutting hair. A freshly cut piece of this material is just as sharp as a modern razor. However, metal razors are also known.

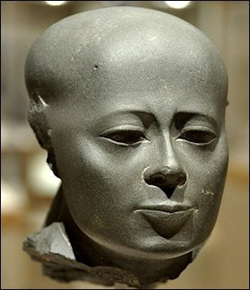

Ancient Greece (900 BC - 600)

Paige Walker describes the changing hair removal habits of the Ancient Greeks throughout ancient Greek history as follows in "Genital Depilation and Power in Classical Greece":

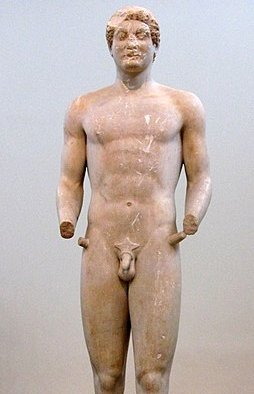

Prior to the beginning of the Classical period, the thriving late Archaic elite proclaimed their superiority through lavishly shaped pubic hair. Although this genital hair removal seems effeminate today, it was part of the representation of the idealised male figure in the late Archaic period at the beginning of the fifth century.

Dynamic trends in the depiction of pubic hair paralleled shifting political tides in ancient Greece :As the Greek poleis overthrew their ruling tyrants and rejected the lavish aristocratic adornment and spending of the social elite, the Greek state wanted to show that it valued the average citizen with both the institution of democracy and the more naturalised depiction of pubic hair. In general, the artistic representation of pubic hair became more naturalistic, replacing the Archaic fan of wildly shaven curls with a simpler and more subtle bar shape.

As democracy flourishes in ancient Greece, this artistic depiction of male pubic hair follows the trajectory towards naturalism. The increasingly free pubic hair on male sculptures from the mid-fifth century exemplifies this development. In representing the male adored figure - be it a god, a hero or an ideal man - the sculptor completely abandoned the depilated form and instead embraced the natural masculinity of the subject.

Literature shows that female genital hair removal was the norm in classical Greece. In Aristophanes "Women in the Thesmophoria", a man tries to disguise himself as a woman to gain entry to the Thesmophoria, an annual religious festival where women gathered secluded from men to worship Demeter. But to successfully pass for a woman, the man must wax his genitals, a requirement that highlights the widespread prevalence of this female grooming convention.

Ancient Rome (753 BC - 476)

The Roman writer and philosopher Seneca wrote in letter 56 to his friend Lucilius:

....you also have to think of the epilator with his shrill and piercing voice with which he wants to stand out and then squeezes everything out of it and never shuts up until he plucks someone's armpits and thus makes another person scream for him.

Seneca also suggests in "Letters to Lucilius 114" that underarm hair removal was normal, but leg hair removal "effeminate":

Yes, some people go wrong as much as others: some are more perfumed than necessary, others more sleazy than necessary; some also depilate their legs, others not even their armpits.

According to Varro, barbers were introduced to Italy from Sicily, in the year of Rome 454, brought over by P. Titinius Mena: before then, Romans did not cut hair. The younger Africanus was the first to adopt the habit of shaving every day. "Africanus sequens; he was the son of Paulus Æmilius, the conqueror of Perseus, and the adopted son of Scipio Africanus. Because of his conquest of Carthage, he was called Africanus the Younger. Aulus Gellius, B. iii. c. 4, refers to his shaving habit. From the remarks of these writers, we can conclude that Romans generally shaved only after the age of forty. The late Emperor Augustus always used razor blades. Suetonius gives another description of how Augustus took care of his beard. After commenting on his carelessness regarding his personal appearance, he says that Augustus sometimes cut his beard, "tonderet", and sometimes shaved it, "raderet". Dion. Cassius mentions the period when Augustus began to shave, the consulate of L. Marcius Censorinus and C. Calvicius Sabinus, Ab Urbe Condita 714; he was then in his twenty-fourth year.

The Ancient Romans had two methods of grooming the beard; in one it was cut close to the skin, in the other it was trimmed with a comb and left at a certain length. These two methods are alluded to by Plautus, Capt. ii. 2, 16:-B. "Now the old man is in the barber's shop; at this moment the other is wielding the razor - but whether to say that he is going to shave him, or to trim him with a comb, I do not know."

Julius Caesar reportedly had "excess hair" plucked from his body, according to a study published in 2014 in the Journal of the History of Sexuality. Ordinary citizens would also have been familiar with depilatories, among other cosmetic products, according to a study published in 2019 in the journal Toxicology in Antiquity.

Medieval period (500-1500)

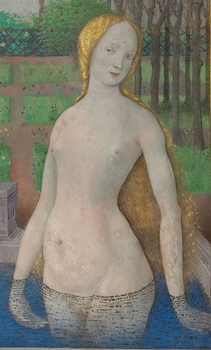

"A Cultural History of Hair in the Middle Ages" by Roberta Milliken suggests that it was the fashion for European aristocratic women to remove their pubic hair. More than one essay quotes a recipe in a widely circulated medical compendium called the Trotula that prescribes a way for noble ladies (nobilibus) to remove their pubic hair using an alarming-sounding preparation of quicklime and orpiment. (The recipe mentions that this mixture burns if left on the skin for too long and prescribes a cooling ointment made of poplar buds and violet oil or house garlic.) According to some versions of the text, the recipe was used by "Saracen noblewomen"; Laura Michele Diener - lecturer in medieval history and women's studies at Marshall University in West Virginia - writes that the fashion for depilating the pubic area "caught on in Europe after encounters of crusaders with hairless Middle Eastern women".

A very interesting passage is one of the texts in the Trotula, De ornatu mulierum (On the adornment of women):

For a woman to become very soft and smooth and hairless from her head down.

A manuscript sheet in the Getty Museum, once part of a prayer book for Louis XII of France, depicts a Biblical scene where Bathsheba is seen bathing while David watches her from a window. To the modern eye, the image looks far too sexy for a religious book. The naked Bathsheba conforms to late medieval aristocratic notions of beauty: she has a high, plucked forehead and long blonde hair that falls behind her in the bathwater and reaches just above her pubic bone. The artist, Jean Bourdichon, did not make the water opaque. Instead, Bathsheba's hands, the tops of her thighs and her vulva are visible under the surface of the water. Pink-red highlights draw attention to her lips, nipples, navel and labia. The glistening of the water makes it clear that she has no pubic hair.

A number of literary texts seem to suggest a link between unkempt pubic hair and low social status. Several works in the pastourelle genre, which usually describe an amorous experience with a peasant woman, contain such themes. Niccolò Campani's "Capitolo delle bellezze della dama" (Chapter on the beauties of the lady) describes a sexual encounter between a peasant and a miller's daughter. The woman's body is described in detail, as in an advertisement for a used car. This is a common trope in courtly poetry, but here she is described from the feet up, rather than the other way round, for comic effect. The imagery is rustic: her feet are big and look like "freshly turned sod"; her thighs are like "hams" and are "hairier than I can tell you - so imagine what that other thing must have been like."

Although tweezing the eyebrows and hairline at the top of the forehead was quite common for many women, the church was very unhappy about this. In Confessional, clergy are encouraged to ask those who come to confession:

If she plucked the hair off her neck, eyebrows or beard for debauchery or to please men This is a mortal sin, unless she does so to remedy a serious deformity or to avoid being rejected by her husband.

The idea that some medieval aristocratic women removed their pubic hair may come as a surprise today. There is a popular misconception that medieval people rarely washed or groomed their bodies as we do, but there is abundant visual and textual evidence to the contrary. Emperor Charlemagne is known to have enjoyed taking steam baths with his family, friends and bodyguards, while the so-called Bad King John reportedly took more baths than any other English king before him. And it was not just the elite who bathed. People in cities may have had access to public baths, which included steam baths (a prescription for hair removal in the Trotula indicates that the treatment had to involve a steam bath), while people in rural areas used streams, pits and rivers for bathing. Research by Barbara Hanawalt - an American historian and best-selling author who specialises in English medieval social history - on records of coroners from medieval England shows that this practice sometimes led to drowning.

Queen Elizabeth formulated the norm for European women during her reign around 1500. She believed that facial hair should always be groomed, with eyebrows being modelled and the hair on the forehead and upper lip removed. Europeans developed a fashion of long foreheads and following suit, women removed all hair from the forehead and were encouraged to raise their hairline an inch. Mothers from rich families rubbed walnut oil and the economically less privileged used bandages soaked in ammonia (which they extracted from their cats' faeces) on their daughters' foreheads to prevent hair growth.

1910-1915

When the 20th century began, women didn't care if they had leg or armpit hair, and it showed in the beauty guides, advertisements and fashion of the time. Clothes were so concealing that you rarely saw bare legs or armpits, so removing hair there was no problem. Before the 1910s, depilatories for these areas were mainly used by actresses or dancers, or for surgical procedures.

Women did worry about hair in other places. Christine Hope did the definitive research on women's hair removal in 1982 with her article "Caucasian Female Body Hair and American Culture" and her examination of ads in old Harper's Bazaar and McCall's magazines shows that they focused on facial, neck and underarm hair. Legs and armpits were nowhere to be seen.

According to Hope, a shift began in 1915 when advertisers in Harper's Bazar began targeting armpit hair (mostly for various depilatory creams). A new trend in sleeveless dresses, often inspired by Greek and Roman clothing, exposed women's previously covered arms. This naturally led the hair removal industry to conclude that armpit hair was undesirable.

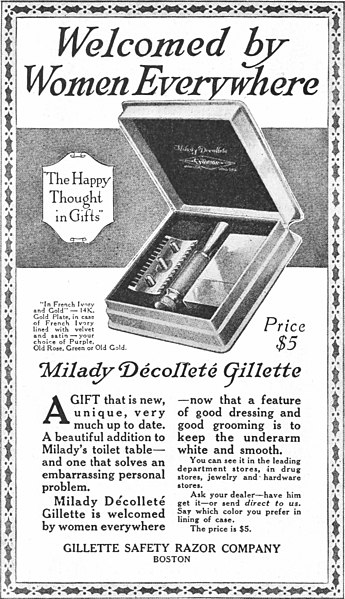

Gillette introduced the first shaver marketed specifically for women, the Milady Decollette, in 1915.

Advertisements touted the razor as a new solution to an "embarrassing personal problem" (hairy armpits) and promoted it as an essential fashion accessory for the "modern woman". Advertisements for razors for women dramatically shaped expectations about hair removal as an everyday part of "womanhood". The trick to getting women to buy the product was to make shaving a new but undeniable part of womanhood. Gillette knew this and so he and his publishers used polarising words in their ads, drawing a hard line between what it meant to be a man and a woman. "As the first company to introduce the concept of shaving for women, Gillette was careful not to be too modern. In their first ads for women, Gillette did not use the word 'shave', but 'smoothing'. 'Shaving' was an activity men did; 'smoothing' was more feminine," explained Kirsten Hansen in her dissertation "Hair or Bare?: The History of American Women and Hair Removal, 1914-1934". "Very few Gillette ads for women used words like 'shave' or 'razor' or 'blade'. The cultural association between men and razors was so deep and old that they had to worry about whether their products were 'feminine' enough," confirms Rebecca M. Herzig, author of "Plucked: A history of hair removal".

To convince women that buying a razor went hand in hand with buying the latest fashion, catalogues began cleverly marketing the two products together. Ads against armpit hair, for example, appeared in McCall's magazine as early as 1917, and razors and depilatories for women appeared in the Sears, Roebuck catalogue in 1922, the same year in which that company began offering dresses with sleeves," explains Anita Renfroe, writer of Don't Say I Didn't Warn You.

Cultural norms, customs and fashions for facial hair in men have changed over time, and innovations and marketing of razors have played a part in this. In the 1800s, shaving was done with a steel razor, often by a barber. When Gillette patented the first safety razor in 1904, it became easier for men to shave themselves at home. As a result, being clean-shaven became both easier and very fashionable.

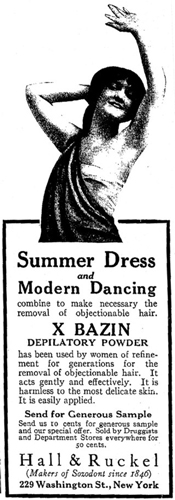

Chemists also sold commercial depilatories, which chemically broke down hairs so that they could be wiped away. A 1908 advertisement for hair removal powder from X-Bazin, titled "Personal Comeliness", stated that the product removed the "misery associated with hair growth on the face, neck or arms". Depilatory powders and creams, however, often irritated the skin. The 1915 ad below in Harper's Bazaar for X Bazin is typical of ads of the time because it describes why underarm hair removal is necessary. It also shows an image of a woman in a sleeveless dress with her arm raised and the caption "Summer Dress and Modern Dancing combine to make necessary the removal of objectionable hair".

In 1919, Neet, the depilatory product we now know as Veet, was founded, and in 1940, Nair. Nair's early depilatory creams contained sodium hydroxide, which chemically broke down hair bonds but could also cause chemical burns. Modern versions of Nair no longer contain this ingredient.

In 1930, Kora M. Lublin founded Koremlu, a hair removal cream in the US based on thallium acetate, an ingredient found in rat poison. While the product destroyed hair, it also poisoned the nervous system. Female users experienced baldness, vomiting, paralysis and damage to the optic nerve. In 1932, women injured by the product sued the company and were awarded damages of more than $2.5 million. However, the then bankrupt company never paid.

1920-1960

With women wanting to keep their armpits smooth, Gillette decided to raise the bar and move the same desire to the legs. After all, the more hair you had to shave, the faster your razor blades would become blunt and the more you would have to buy. But the trick didn't really work. As fashion in the 1920s showed some shin and hemlines going up, nylon stockings also came into fashion. "In the April 1929 edition of Harper's Bazaar, there were eight ads for eight different brands of nylon stockings, while there was only one ad for leg hair removal. Although no such fashion existed for the problem of armpit hair, wearing stockings seemed a quick, hassle-free solution to leg hair," Hansen mentions. While there wasn't much you could do to hide hair if you crossed your arms in a Charleston, there was an easy way to hide leg hair. And since shaving was messy and required a lot of maintenance, women didn't find it necessary to bother.

Shorter hems in the 1930s and 1940s and a shortage of nylon stockings during World War II caused more and more American women to shave their legs too.

Nylon and silk were needed to make parachutes and war uniforms and so women had to resort to wearing liquid stockings - tights that were "thick, coloured lotions designed to create the illusion of fabric for women who did not like to appear with bare legs". The point, however, was that leg dye only worked if you had smooth legs. According to a women's magazine of the time, "the best liquid stockings available will not fool anyone unless the legs are smooth and free of hair or stubble. Leg make-up becomes matt or sticky on the hairs and detours around the stubble and gives a streaky appearance," according to a women's magazine of the time.

But after a while, more and more women decided that shaving their legs and leaving them bare was much easier and cheaper than lotions or messy powders. This continued well into the post-war years, at a time when nylons were again available in department stores.

Manufacturers of hair removal products initially focused their marketing on the upper class. From 1934, a similar type of advertisement appeared in the middle-class Ladies' Home Journal that had been in the upper-class Harper's Bazaar for the previous 15 years (Hansen, K. (2007). "Hair or Bare? The History of American Women and Hair Removal, 1914-1934").

The introduction of the bikini in the US in 1946 also led shaving companies and female consumers to focus on trimming and shaping their lower legs. In May 1946, Parisian fashion designer Jacques Heim released a two-piece swimming costume design that he called the Atome ('Atom') and advertised as "the world's smallest swimming costume". Like swimming costumes of the time, it covered the wearer's navel and did not attract much attention. Clothing designer Louis Réard introduced his new, smaller design in July. He named the swimming costume after the Bikini atoll where the first public test of an atomic bomb had taken place four days earlier. His scanty design was edgy, showing the navel and a large part of the wearer's buttocks. No fashion model wanted to wear it, so he hired a nude dancer from the Casino de Paris called Micheline Bernardini to show it off.

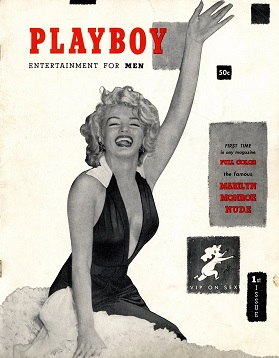

In the 1950s, when Playboy was on newsstands (the first issue came out in 1953), clean-shaven, lingerie-clad women set a new standard for the term "sexy".

From then on, shaving became a widespread practice among women in the United States. Rebecca Herzig, the author of Plucked: A History of Hair Removal, states the following:

"By 1964, surveys indicated that 98 per cent of all American women between the ages of fifteen and forty-four shaved their legs regularly."

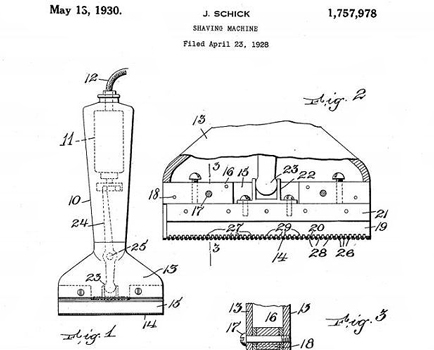

On 13 May 1930, Colonel Jacob Schick was granted patent no. 1,757,978 for his dry electric shaver. He came up with the idea of developing an electric shaver while recovering from an injury he sustained during a gold prospecting expedition in Alaska and British Columbia in the early 1910s. Schick found it difficult to shave while having time on his hands during his recovery period. So he made rough plans for a shaver with a shaving head powered by a flexible cable and driven by an external motor the size of a grapefruit.

In the late 1940s, the first battery-powered electric shavers entered the market. In 1960, Remington introduced the first battery-powered rechargeable electric shaver.

The prototype "ruby" laser, invented by Theodore H Maiman in 1960, consisted of a silver-coated ruby wand - it was revolutionary but unreliable. The continuous laser beam not only burned and damaged the skin, but was also slow and labour-intensive because only a few follicles were treated at a time. Due to frequent burning of surrounding tissue, the device was eventually recalled. Safety improvements were made, but changing the heat intensity meant that follicles were not efficiently destroyed and grew back.

1960-Present

Following theoretical treatises by M.G. Bernard, G. Duraffourg and William P. Dumke in the early 1960s, coherent light emission from a laser diode was demonstrated in 1962 by two US groups led by Robert N. Hall at General Electric's research centre and by Marshall Nathan at the IBM T. J. Watson Research Centre. There is ongoing debate as to whether IBM or GE invented the first laser diode. Priority is given to the General Electric group, which obtained and submitted its results earlier.

The Nd:YAG laser was invented by J.E. Geusic at Bell Laboratories in 1964.

Although electrolysis had been around for almost a century, it became more reliable and safer in the 1970s with the development of transistor devices.

The next laser development came in the 1970s when the Alexandrite laser was invented. Rays were forced through an alexandrite crystal, reducing hair growth. Although these lasers were much safer, they did not deliver enough heat to destroy the hair follicle. As a result, it would have taken years to achieve permanent results.

Although Playboy flaunted its female beauties, feminists of the 1960s and 1970s turned their backs on the ideal of the hairless body in favor of women au naturel. Around that time, there was the second feminist wave and the spread of hippie culture, both of which rejected hairless bodies. For many women, body hair was the symbol of their struggle for equality. However, the rejection proved short-lived.

Salons began depilating more than just legs and armpits. We have to thank Manhattan's J. Sisters Salon for popularizing the Brazilian wax in the 1980s, forever changing the way we think about pubic hair. This style reached Hollywood celebrity status when Carrie Bradshaw accidentally got a Brazilian wax in an episode of "Sex and the City" season 3 in 2000.

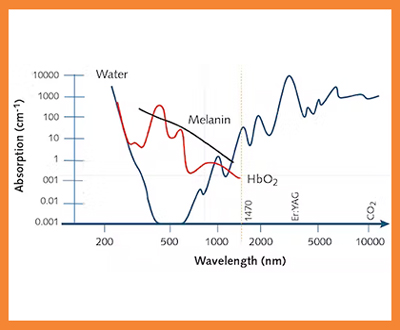

The theory of selective photothermolysis developed by Richard Rox Anderson and Parrish in 1983 was based on a laser with a particular wavelength and pulse duration of light to target a particular chromophore. By applying this theory, the target (a selective type of tissue) could be selectively destroyed, sparing the surrounding tissue. (Anderson RR, Parrish JA. Selective photothermolysis: precise microsurgery by selective absorption of pulsed radiation. Science. 1983 Apr 29. 220(4596):524-7.). This theory would prove to be the basis of laser hair removal.

Richard Rox Anderson worked at Harvard Medical School and had recently hired a new physician for his team, Dr. Melanie Grossman. Grossman suggested they investigate laser hair removal, referring to previous research on lasers and ineffective results. Anderson and Grossman began tests on furry dogs, and in 1994 they published their first paper on laser hair removal on human subjects. Anderson was the first of their human trials, in keeping with his golden rule: "Do unto yourself before you do unto others." Anderson's specific laser hair removal technique would lay the foundation for modern laser hair removal as we know it today. Although the process was generally similar to earlier studies decades earlier, Anderson and Grossman had perfected the duration and intensity of the laser applied to the skin. Due to Anderson and Grossman's success with laser hair removal technology, the method was later approved by the FDA in 1997. Anderson would go on to invent and develop many more laser treatments, including those for removing tattoos, pigmented lesions, birthmarks and more.

Interview Richard Rox Anderson

'Inventor' of laser hair removal

In the early 2000s, much of how society thought about pubic hair had to do with clothing style. With cropped tops and low-waisted jeans, women were more likely to have a Brazilian bikini wax done (or have everything underneath removed) because the trendy styles caused them to show more skin. The magazine industry portrayed women as hairless and airbrushed them.

Male hair removal in the 21st century

Although modern men seemed to have escaped the dance at first, hair removal seems to be becoming the norm with them as well. If you look around you on the beach you will see plenty of hairless torsos. Curiously enough, then, little research has been done on male hair removal. In 2014, American researchers at Lafayette College did make an attempt:

Young men in Western cultures often engage in body hair removal, but little is known about how such bodies are perceived. In this exploratory study, American students (N=238) were asked to view six photographs of the same male body with varying amounts of visible body hair and indicate which body was most sexually attractive to themselves, to most men and to most women. Both men and women chose a relatively hairless male body as the most sexually attractive. Women, however, thought men would choose a hairier body than men actually did.